Eugene Debs held memberships and official positions in two late 19th century labor unions: the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen (BLF) and the American Railway Union (ARU). Later, he joined a group of labor radicals to found the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). Debs promoted workers’ right to organize unions and to strike in order to protect their interests, for shorter hours, and for restrictions on child labor.

Debs was a charter member and first secretary of the Terre Haute chapter of the BLF. Joshua Leach came to Terre Haute from St. Louis to form Vigo Lodge #16, and although Debs by this time had left railroad work and was employed as a clerk in the Hulman grocery business, Debs was allowed to join. Seeing Debs energy and enthusiasm, soon afterwards Leach is alleged to have said: “I put a tow-headed boy in the brotherhood at Terre Haute not long ago, and some day he will be at the head of it.” An accurate prophesy, for Debs established himself as one of the nation’s most successful union leaders and organizers whose reputation spread far beyond the BLF membership.

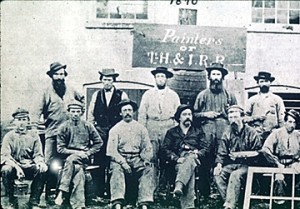

Debs was appointed editor of the BLF Magazine, where the power of his journalism became evident and caused the readership of the Magazine to spread well beyond the brotherhood’s membership, making it a foremost labor voice at a time when the printed word had no competition from such media as radio and television. In 1880, Debs was named Grand Secretary- Treasurer of BLF, a post he held until he stepped down in 1891, but was prevailed upon to continue editorship of the Magazine.

Debs left the BLF because of frustration over the ineffectiveness of the brotherhoods. Being organized along craft lines in the railroad industry, with separate brotherhoods for brakemen, firemen, telegraphers, switchmen and so on, the owners easily could break a strike or job action of one brotherhood by hiring replacement workers. Debs saw the need for an industry-wide union organization which would unite all the workers on the railroads. So, in 1893, in Chicago, Debs founded the American Railway Union (ARU). Due largely to Debs’ established reputation and widespread recognition among workers, to say nothing of his tireless efforts and boundless enthusiasm, the ARU achieved phenomenal organizing success and membership expanded rapidly at a time when other labor unions were struggling just to stay alive.

In 1893, the ARU called a strike against the Great Northern Railroad, which was an extremely important railroad carrying freight and passengers west from Milwaukee to the Pacific Northwest. The strike was settled after 18 days and a contract signed which met virtually all union demands.

Perhaps this success gave the ARU membership an excessive sense of optimism and power, which would prove to be the union’s undoing. When the ARU met in May, 1894, at its annual convention in Chicago, a delegation of desperate employees and their families from Pullman City came with an appeal for support in their struggle with the Pullman Company

The so-called “Pullman Boycott” grew out of the ARU’s sympathy for the plight of laid off workers and reduced wages, but with no reduction in rent or prices for groceries at the company store where they were required to shop. Debs advocated caution and urged efforts at mediation before the ARU took on the Pullman company. After all, these workers produced sleeping cars; they were not railroad workers.

Debs’ words of caution went unheeded, besides, the Pullman executives refused all efforts at mediation, so Deb had no choice but to lead the ARU in the boycott. The Pullman Company did not have to go it alone against the ARU as had the Great Northern. The full force of support from all the railroad company owners plus the Federal government, including the legal system and the national guard, not to mention solid support form the press, were all marshalled in a solid front aimed at breaking the strike and destroying the up-start union. The ARU got virtually no support from other unions or the Gompers led American Federation of Labor. The result was total disaster for the ARU. The strike was broken. Debs and other ARU officials were sentenced to a year in jail for having violated injunction against the strike. (The same judge who had issued the injunction passed judgment and sentence on the ARU officials.) Robbed of its leadership, its members blacklisted everywhere making it impossible to find work on the railroads, the ARU never recovered.

Debs served time in prison twice during his life: once in 1895, served in Woodstock jail, Illinois for his actions as union leader, and again after World War I, in Atlanta Federal Prison, for violating the Espionage Act by speaking out against our involvement in the war.

This ended Debs’ career as a union leader. He had come to see that changes would have to be made in our political and legal institutions before unions could succeed in protecting workers rights, so the rest of his life was spent in the political arena. But Debs had succeeded in demonstrating what role the industrial type of union could play in a society where workers’ rights could be protected. So the ARU remained as an example of the superior type of union organization which united workers by industry rather than by interests of craft or skill.

That Debs was no longer a union leader did not mean that his continued interest in workers’ rights would be expressed only in political activities. Wherever and whenever workers were in confrontation with owners, Debs was likely to show up to offer support and encouragement. In many a coal field action, for example, Debs would be there to work with and encourage the striking men, and legendary Mother Jones would focus on working with the strikers’ wives and families. Debs was there to show support in the infamous Ludlow, Colorado disaster, where the Rockefellow owned mining company hired gunmen to shoot up and burn the tent city in which the miners and their wives and children were living. Some 25 women and children perished, a public relations nightmare for Rockefellow. In summary, half of Debs’ adult life was spend as union leader, and the remaining half was spent attempting to advance workers’ rights through the political arena, advocating the right to organize and to strike, restrictions on child labor, and job security. Also, at one brief point in the “political half’ of his career, Debs joined with Bill Haywood and Mother Jones, in 1905, to found the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). The IWW was seriously divided by every shade of radical opinion, including Haywoods syndicalism, Mother Jones trade unionism, and Lucy Parsons’ anarchism, and Debs’ disagreement with the leadership over numerous issues, including Debs’ insistence on nonviolence, led him to drop out of that organization after a few years.

Suggested Reading

Ray Ginger, The Bending Cross. Rutgers University Press, 1949.

Reprinted by The Thomas Jefferson University Press at Northeast Missouri State University, 1992. By far the most descriptive and detailed of the accounts of Debs’ life, the reprint edition was brought out by the Debs Foundation. It includes numerous photographs of Debs’ life and an introduction by J. Robert Constantine.

William H. Carwardine, The Pullman Strike. Charles H. Kerr Publishing Company, 1894 and 1973.

Nick Salvatore, Eugene V. Debs: Citizen and Socialist. University of Illinois Press, 1983.

Jack Kelly, The Edge of Anarchy: The Railroad Barons, the Gilded Age, and the Greatest Labor Uprising in America. St. Martin’s Press, 2019.

Paul Buhle, Steve Max, Noah Van Sciver, & Dave Nance, Eugene V. Debs: A Graphic Biography. Verso, 2019.

Theodore Debs, Sidelights in the Life of Debs.